Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease which remains incurable. The disease is characterized by the selective degeneration of upper motor neurons in the motor cortex as well as the lower motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord. The cause of ALS remains unknown in 90 percent of cases, which are referred to as sporadic ALS because there is no family history for the disease. Cumulative evidence suggests that sporadic ALS may result from complex interactions between genetic susceptibility and aging.

The remaining 10 percent of ALS cases are hereditary and linked to mutations in one of over 30 distinct genes involved in different cellular processes. There are severe early-onset and juvenile cases, the majority of which are caused by mutations in the FUS gene. FUS is a protein widely expressed across tissues and has a role in various DNA and RNA processing steps, including DNA repair, transcription, RNA splicing, and nucleo-cytoplasmic RNA shuttling. However, mutations in this protein particularly affect motor neurons in ALS.

Professor Dr David Vilchez and his team at the University of Cologne’s CECAD Cluster of Excellence for Aging Research identified two proteins interacting with an ALS-causing mutant FUS variant (FUS P525L) by investigating motor neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC). Their results indicate that inhibiting those interacting proteins could be a possible therapeutic target for familial cases caused by mutations in FUS. The study was published under the title ‘ALS-FUS mutations cause abnormal PARylation and histone H1.2 interaction, leading to pathological changes’ in Cell Reports.

The two proteins which interacted with the mutant FUS protein were PARP1, an enzyme promoting poly ADP-ribosylation (PARylation), a modification that can alter proteins in different ways, and histone H1.2, a protein involved in wrapping the cells’ DNA in their known shape of chromosomes. In further experiments in the human motor neuron cells, the researchers found that inhibiting PARylation or reducing H1.2 levels alleviates ALS-related changes such as the aggregation of mutant FUS protein and neurodegeneration.

Next, the scientists conducted experiments using the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as a model of ALS. They found that when the worms’ orthologs of the human proteins PARP1 and H1.2 were knocked down, the aggregation of mutant FUS and neurodegeneration also decreased. The scientists also observed that ALS-related changes worsen when these two proteins were overexpressed in C. elegans. “Considering all our data, our findings indicate a link between PARylation, H1.2 and FUS with potential therapeutic implications,” said Dr Hafiza Alirzayeva, first author of the study.

According to the researchers, the pathology between familial ALS, on which this study focused, and sporadic ALS is very similar: Although FUS is mutated in certain familial cases, non-mutant FUS aggregates in many sporadic cases as well. Professor Dr David Vilchez, Principal Investigator at CECAD, said: “Most basic research focuses on the mutant genes that cause familial ALS because at least we know those genes. But we hope to show in further studies that our findings could have a potential impact on sporadic ALS as well, since that is the form that affects the overwhelming majority of patients.”

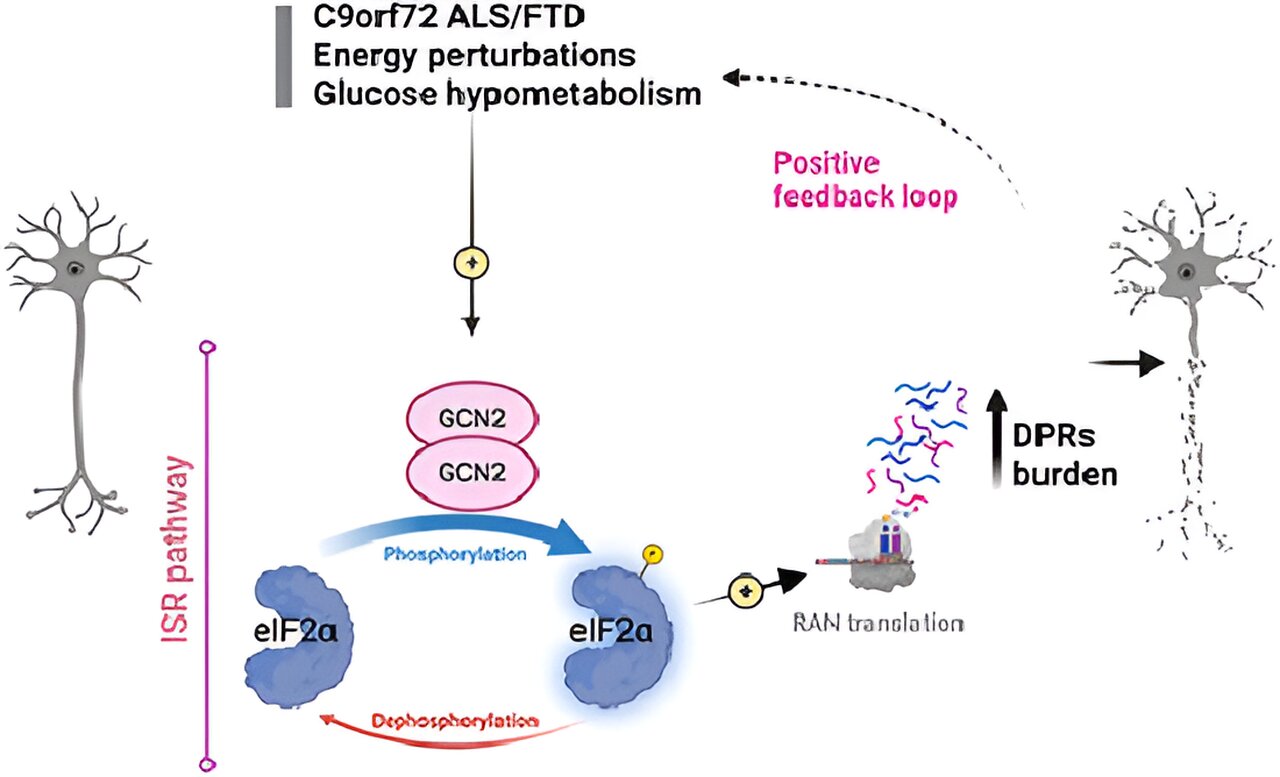

In future work, the authors will study whether these proteins could also be involved in ALS-related changes associated with other genes that cause the disease such as TDP-43 and C9orf72, as well as those of sporadic ALS.