Researchers at the University of Bonn and the University of Cambridge have identified an important control circuit involved in the eating process. The study has revealed that fly larvae have special sensors, or receptors, in their esophagus that are triggered as soon as the animal swallows something. If the larva has swallowed food, they tell the brain to release serotonin. This messenger substance—which is often also referred to as the feel-good hormone—ensures that the larva continues to eat.

The researchers assume that humans also have a very similar control circuit. The results were published in the journal Current Biology.

Imagine you are hungry and sitting in a restaurant. There is a pizza on the table in front of you that smells extremely inviting. You take a bite, chew and swallow it and feel elated at that precise moment: Oh boy that was tasty! You quickly cut the next piece of the pizza and cram it into your mouth.

The smell of the pizza and how it tastes on your tongue motivates you to start your meal. However, it’s the good feeling you have after swallowing that is largely responsible for you continuing to eat.

“But how exactly does this process work? Which neural circuits are responsible? Our study has provided an answer to these questions,” says Prof. Dr. Michael Pankratz from the LIMES Institute (the acronym stands for “Life & Medical Sciences”) at the University of Bonn.

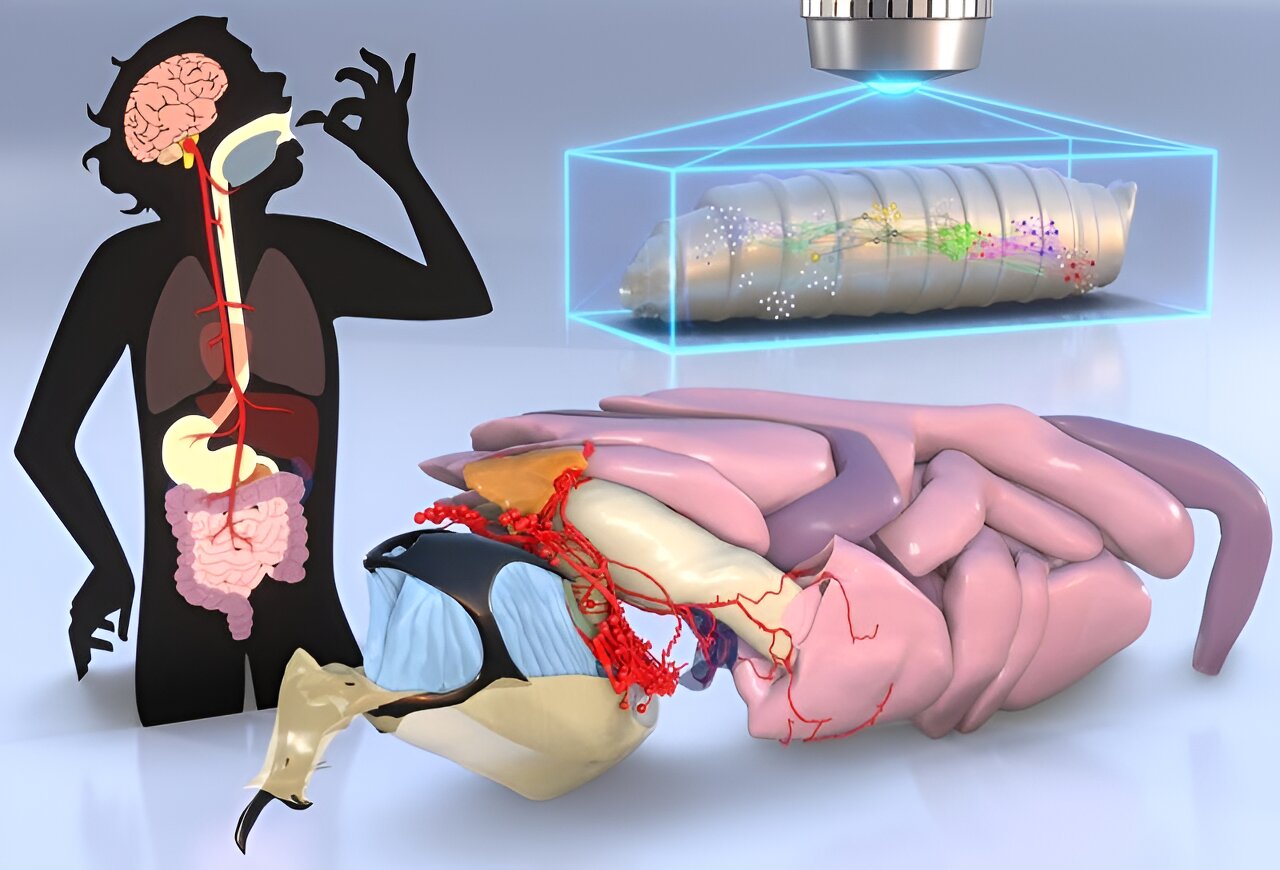

The researchers didn’t gain their insights from humans but instead by studying the larvae of the fruit fly Drosophila. These flies have around 10,000 to 15,000 nerve cells—which is a manageable number compared to the 100 billion in the human brain.

However, these 15,000 nerve cells already form an extremely complex network: Every neuron has branching projections via which it contacts dozens or even hundreds of other nerve cells.

All nerve connections in fly larvae investigated for the first time

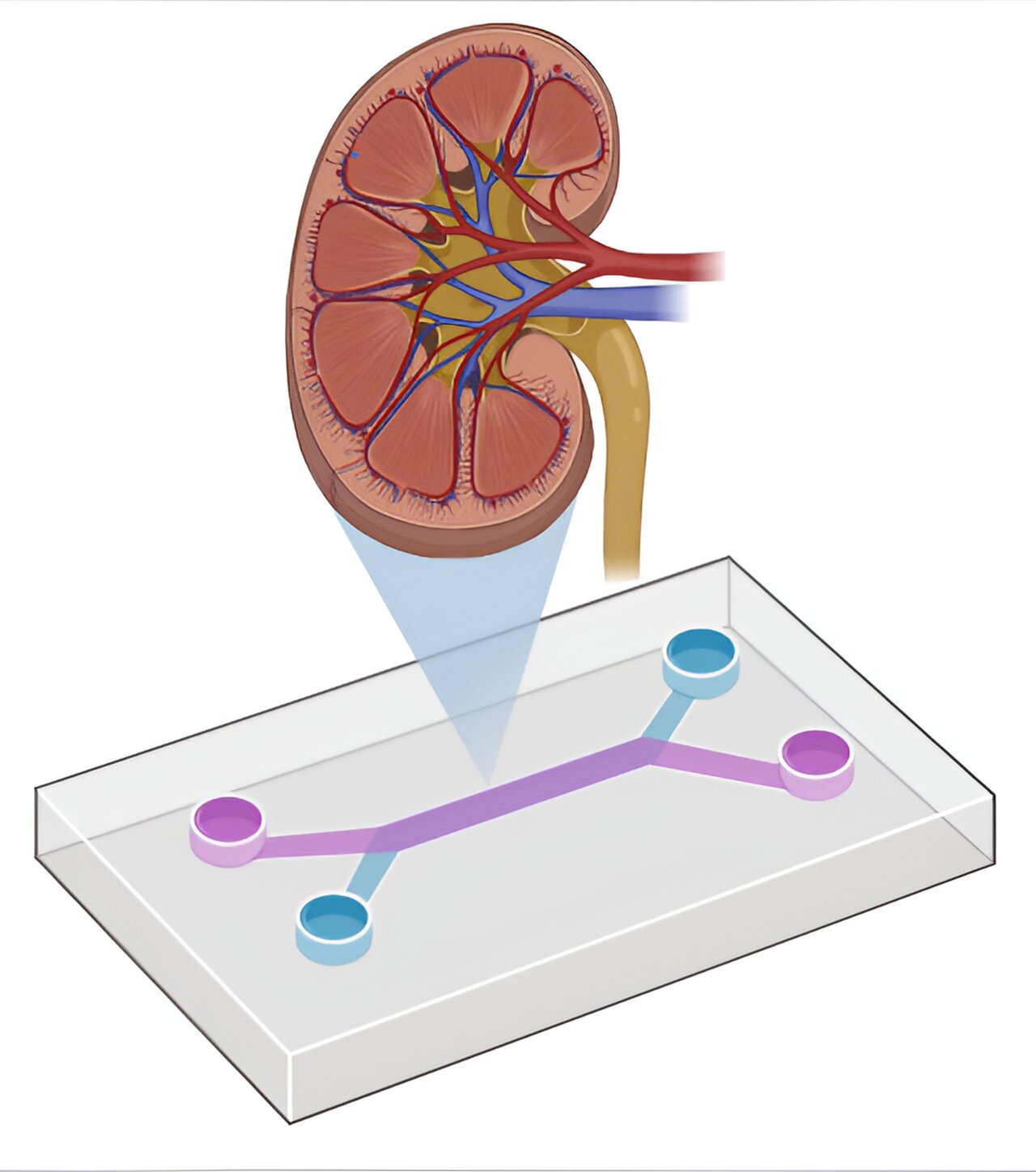

“We wanted to gain a detailed understanding of how the digestive system communicates with the brain when consuming food,” says Pankratz. “In order to do this, we had to understand which neurons are involved in this flow of information and how they are triggered.”

Therefore, the researchers analyzed not only the paths of all of the nerve fibers in the larvae but also the connections between the different neurons. For this purpose, the researchers cut a larva into thousands of razor-thin slices and photographed them under an electron microscope.

“We used a high-performance computer to create three-dimensional images from these photographs,” explains the researcher, who is also a member of the transdisciplinary research area “Life and Health” and the “ImmunoSensation” Cluster of Excellence.

The next step was a real herculean task. The project assistants Dr. Andreas Schoofs and Dr. Anton Miroschnikow investigated how all the nerve cells are “wired” to one another—neuron for neuron and synapse for synapse.

The stretch receptor is wired to serotonin neurons

This process enabled the researchers to identify a sort of “stretch receptor” in the esophagus. It is wired to a group of six neurons in the larva’s brain that are able to produce serotonin. This neuromodulator is also sometimes called the “feel-good hormone.” It ensures, for example, that we feel rewarded for certain actions and are encouraged to continue doing them.

The serotonin neurons receive additional information about what the animal has just swallowed. “They can detect whether it is food or not and also evaluate its quality,” explains the lead author of the study, Dr. Andreas Schoofs. “They only produce serotonin if good quality food is detected, which in turn ensures that the larva continues to eat.”

This mechanism is of such fundamental importance that it probably also exists in humans. If it is defective, it could potentially cause eating disorders such as anorexia or binge eating. It may therefore be possible that the results of this basic research could also have implications for the treatment of such disorders.

“But we don’t know enough at this stage about how the control circuit in humans actually works,” says Pankratz. “There is still years of research required in this area.”

More information:

Andreas Schoofs et al, Serotonergic modulation of swallowing in a complete fly vagus nerve connectome, Current Biology (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.08.025

Citation:

Swallowing triggers a release of serotonin, research reveals (2024, September 13)

retrieved 13 September 2024

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-09-swallowing-triggers-serotonin-reveals.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.