Five years ago, at the outset of the coronavirus pandemic, a phenomenon became abundantly clear: Preschool-age children rarely developed severe cases of COVID-19.

It wasn’t that children under the age of 5 were avoiding infection. To the contrary, they were coming down with COVID like everyone else. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that more than 90% of children from infancy through age 17 have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID.

What made the youngest population of children different is their generally striking avoidance of severe coronavirus infection. That fact has led scientists worldwide to seek an answer to a deceptively simple question: How does the youngest population of children, no matter where they are in the world, continually elude severe COVID?

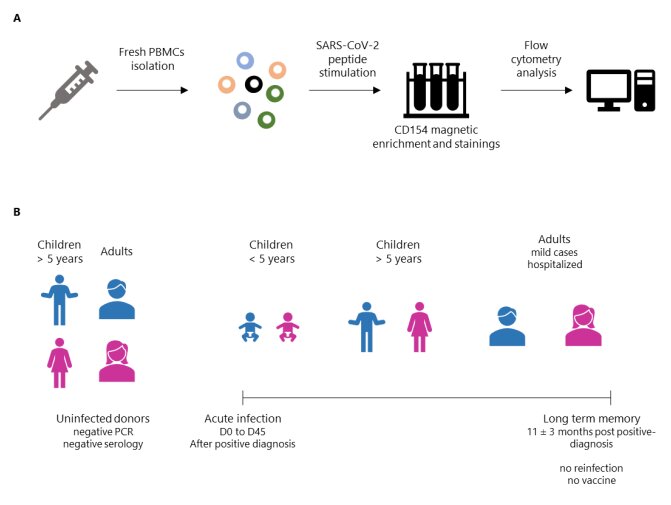

Now, a large team of immunologists and physician–scientists from multiple institutions in France has conducted an in-depth study that compares the immune response of preschoolers to older children and adults. The team focused on the adaptive immune response—the activities of T cells and B cells—to understand how the youngest among us are generally spared from severe, even fatal infections.

“The primary risk factor for severe [coronavirus] disease is age,” writes Dr. Benoît Manfroi, lead author of the research, published in Science Translational Medicine. “Children show the lowest risk, and older adults are the most vulnerable,” Manfroi added.

With other viral infections, the most susceptible populations are generally at two extremes in age: the very young and the very old. The research team pointed to influenza and respiratory syncytial virus—RSV—as just two of multiple viruses that cause significant morbidity and mortality in the two vulnerable age groups.

That rule of thumb fails to apply, however, when the infection is caused by SARS-CoV-2, or any other coronavirus capable of causing severe infections. In the United States, the CDC characterizes preschoolers’ relationship with SARS-CoV-2 in another way—with statistics. Kids under age 5 represent 6% of the total U.S. population, yet only 0.1% of COVID-19 deaths have occurred in this age group. Preschool-age children who have developed severe COVID tend to have comorbidities, studies have shown.

To better understand the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in preschool-age children, the French team conducted a wide-ranging study that included people of all ages, 89 participants altogether. Included were preschoolers, older children, and adults with mild or severe COVID before, during, and 11 months after infection. Scientists collected data on adaptive immune responses, also known as acquired immunity, or pathogen-specific immune responses.

During SARS-CoV-2 infection, children under age 5 had a lower and phenotypically distinct antiviral CD4+ T cell response compared with older children and adults with mild disease. This younger cohort also developed phenotypically distinct memory T and B cell responses after recovery compared with participants from other age groups.

For example, preschoolers’ unique memory T cells had marked inflammatory features compared with other cohorts. And their virus-reactive memory B cells were fewer in number than those of older children and adults.

Differences in the immune responses of older children and adults, the French analysis found, reflect the maturation of the immune system. Manfroi and colleagues suggest the beneficial immune response unique to preschoolers allows them to consistently avoid severe infection.

“The immune systems of preschoolers are subjected to unique external influences, being more frequently exposed to microbes compared with those of adults, especially to respiratory viruses, including endemic human coronaviruses,” added Manfroi, referring to the four known coronaviruses that cause the common cold.

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 wasn’t the first time that medical scientists observed extremely young patients avoiding severe disease caused by a coronavirus. Children under age 5 were generally spared severe infection when exposed to SARS-CoV-1, the coronavirus that triggered a 2002–2003 outbreak. Infections began in China before spreading elsewhere in Asia. SARS-CoV-1 also spread to North America and South Africa.

The World Health Organization estimated the mortality rate for younger adults was between 10% and 15%, but among people 65 and older, mortality exceeded 50%. The generally mild disease in children under the age of 5 took medical scientists by surprise.

“Host resistance to infectious diseases is largely determined by the immune system, which takes several years to mature after birth. Infants initially rely on maternal antibodies and innate immunity because the innate immune system matures faster than its adaptive counterpart,” asserted Manfroi, who was among dozens of scientists conducting an arm of the research at INSERM, or Insitut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale in Paris.

Other collaborators were from Institut Necker Enfants Malades; Institut Pasteur; Hôpitaux Universitaires Paris; Sorbonne Université, and Université Paris Cité, among other research centers. Outside of France, team members hailed from Germany and Guyana.

The French results arrive on the heels of an American-led study published in the journal Cell in 2023. Scientists at Stanford University in California led an international team that also concluded preschool-age children have milder cases of COVID-19.

The Stanford research found that among adults infected with SARS-CoV-2, antibodies specific to the virus rose quickly, then dropped off dramatically, declining 10-fold in six months.

Infants’ antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 rose slower and never dropped. Antibodies either stayed at the same level or continued to rise throughout a 300-day observation period.

Dr. Bali Pulendran, lead investigator, attributed preschoolers’ mild bouts with COVID to an abundance of inflammation-promoting proteins—cytokines—in the nasal cavity. Key among those proteins was alpha-interferon, which is noteworthy for shutting down viral replication in infected cells, Pulendran said in a statement.

Manfroi and colleagues, meanwhile, acknowledge that their study had several limitations. “A first major limitation lies in the lack of assessment of tissues other than blood, particularly of mucosal sites using either nasal swabs or biopsies from adenoids or tonsils,” the team concluded, noting it “has been reported using swab samples that infants and young children have robustly up-regulated expression of inflammatory cytokines at mucosal sites during the acute phase of infection compared with adults.”

More information:

Benoît Manfroi et al, Preschool-age children maintain a distinct memory CD4 + T cell and memory B cell response after SARS-CoV-2 infection, Science Translational Medicine (2024). DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adl1997

© 2024 Science X Network

Citation:

In depth analysis explains why preschoolers are less likely to develop severe COVID-19 (2024, October 15)

retrieved 16 October 2024

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-10-depth-analysis-preschoolers-severe-covid.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.