Researchers have identified the skin cells responsible for orchestrating cases of two of the most life-threatening drug reactions. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) cause the skin and mucous membranes to blister and detach, and carry an average mortality rate of 20%.

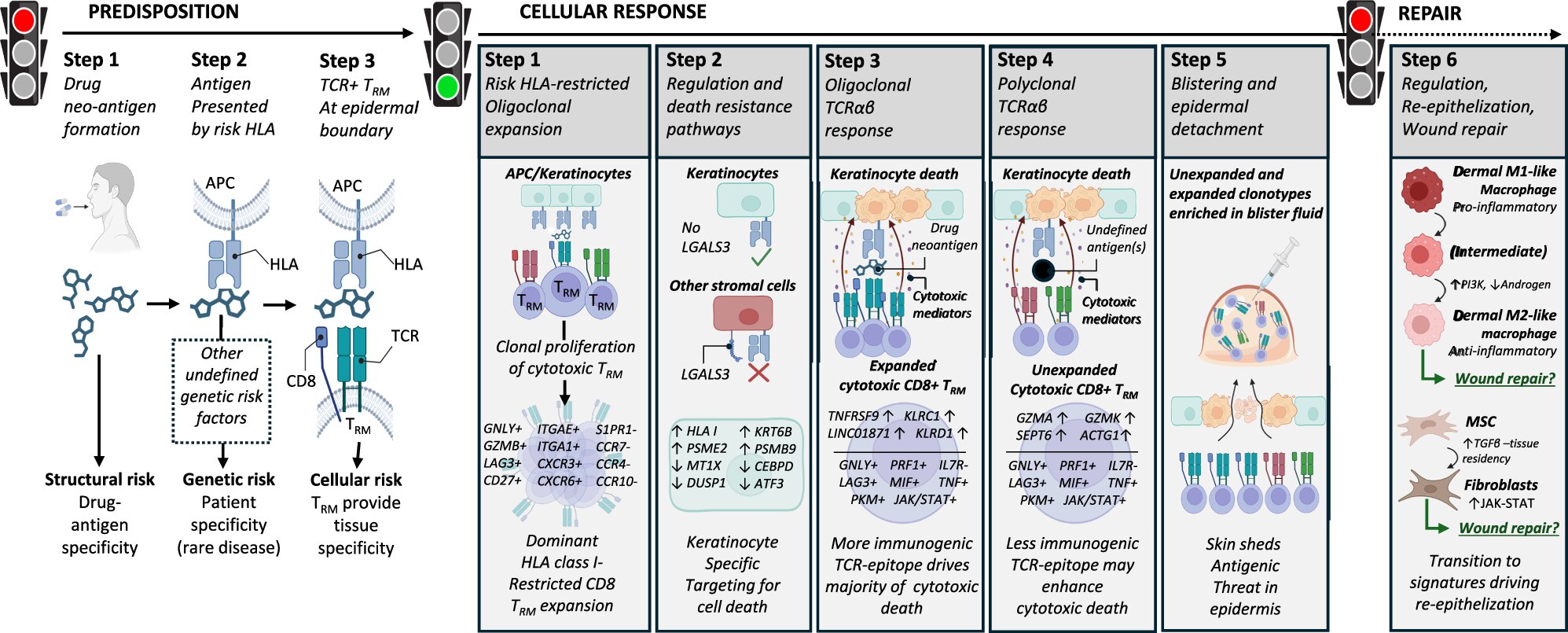

In a study published in Nature Communications, researchers reveal that cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells, which are activated and armed within the skin itself, target and kill the very skin cells (keratinocytes) that enable their activation.

For the first time, advanced single-cell multi-omic sequencing techniques were used to analyze the skin and blister fluid of SJS/TEN patients, and this approach identified previously unknown cellular and molecular signatures and interactions between immune cells and skin cells that drive the destructive process.

Professor Elizabeth Phillips MD, Director of the Center for Clinical Pharmacology at Murdoch University’s Institute for Immunology and Infectious Diseases (iiid), said the findings could lead to tools for both earlier diagnosis and more targeted and effective treatments for sufferers of SJS/TEN.

“One of the most intriguing findings of the study is that the skin or epidermal cells known as keratinocytes play a key role in arming the T cells. Keratinocytes not only activate the CD8+ T-cell assassins, but they also seem to lose some of their natural defenses,” Professor Phillips said.

“This creates a self-destructive cycle where the very cells responsible for protecting the skin are turning the immune system against themselves.”

Although these CD8+ T cells only expand in the skin after exposure to the triggering drug, Professor Phillips said that previous work from this research group demonstrated that for certain drugs, HLA typing can be used preventively to identify individuals at risk of developing SJS/TEN by avoiding their exposure to the drug.

“This is a major step forward in understanding and combating rare but severe drug reactions, bringing hope to patients and families affected by these devastating conditions,” Professor Phillips said.

More information:

Andrew Gibson et al, Multiomic single-cell sequencing defines tissue-specific responses in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-52990-3

Citation:

‘Assassin’ cells found to play a key role in deadly drug reactions (2024, October 28)

retrieved 28 October 2024

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-10-assassin-cells-play-key-role.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.