A new study found that pregnant people in Massachusetts who made multiple unscheduled hospital visits during their pregnancy were 46 percent more likely to experience severe maternal morbidity than those who sought limited or no emergency care during pregnancy.

Frequent hospital visits during pregnancy could be a sign that a pregnant person will encounter life-threatening complications during or after pregnancy, according to a new study led by Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH) and Cityblock Health.

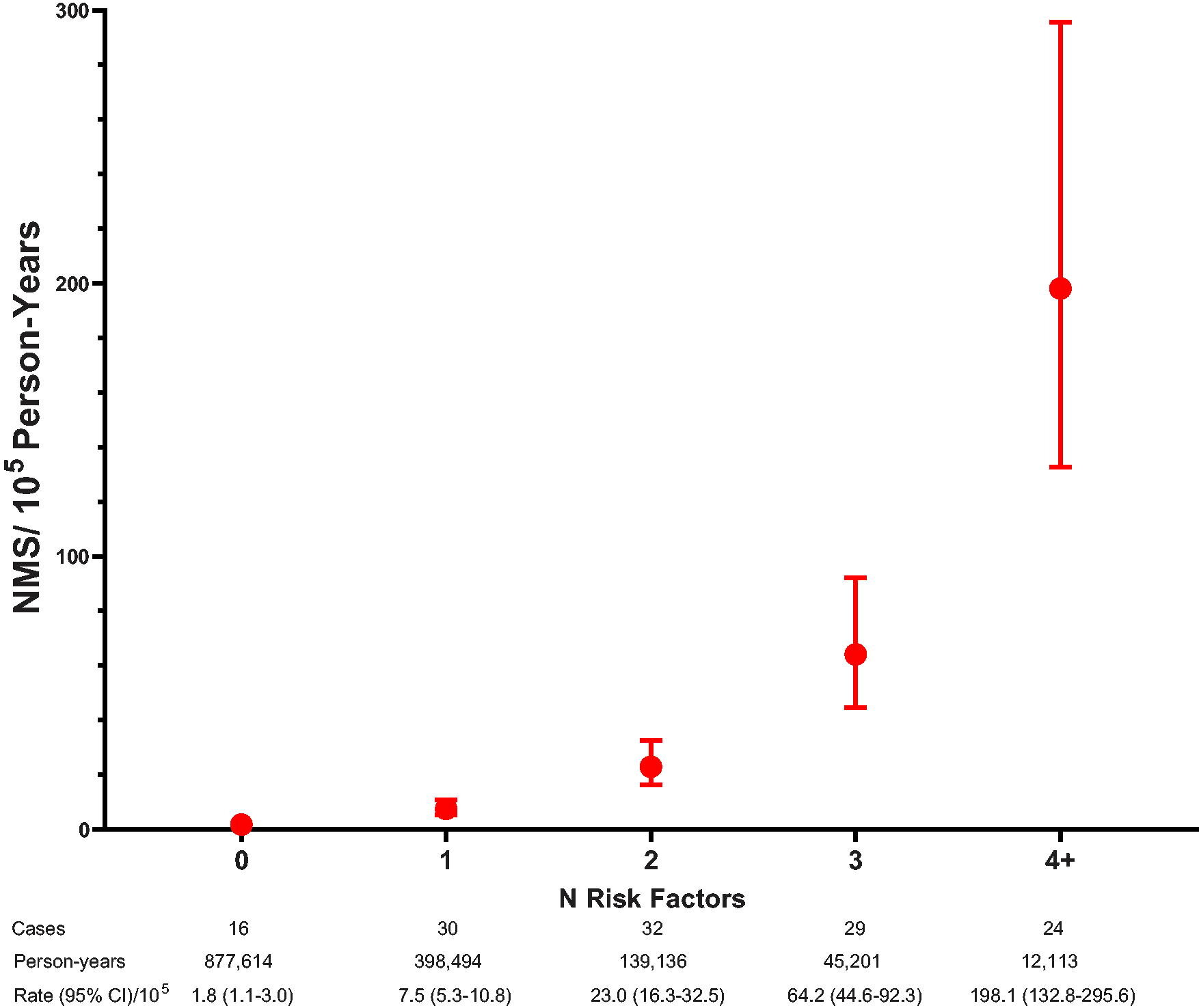

Published in JAMA Network Open, the study found that, among nearly 775,000 pregnant people in Massachusetts, 31 percent of these individuals had at least one unscheduled emergency visit to the hospital, and 3.3 percent had four or more unscheduled hospital visits. The latter group was nearly 50 percent more likely to experience severe maternal morbidity (SMM), which encompasses a range of complications during labor or childbirth that can lead to poor maternal outcomes such as aneurysms, eclampsia, kidney and heart failure, and sepsis.

Importantly, the findings also revealed that nearly half of the pregnant people who sought emergency care four or more times during their pregnancy visited multiple hospitals for evaluation. The resulting lack of consistent treatment to patients from any given hospital makes it difficult for hospital-based pregnancy programs to capture the true burden of prenatal and postpartum challenges that these patients experience.

The analysis is the first US-based assessment of an association between four or more emergency-care visits during pregnancy and risk of SMM. It builds upon a prior study by the researchers which found that 70 percent of people who had a pregnancy-associated death during postpartum also visited a hospital between the time they gave birth and the time they were hospitalized at death. As both SMM and maternal morbidity rates in the US remain the highest among wealthy countries, identifying these high-risk pregnant patients and understanding the extent of their prenatal health challenges can spur efforts to connect this population to other preventive care within their communities.

“When there is a poor maternal health outcome, there is a tendency to say, ‘If we only knew earlier,’says study lead author Dr. Eugene Declercq, professor of community health sciences at BUSPH. “Those in our study with repeated prenatal emergency visits are showing us clearly they’re at risk. Avoiding severe maternal morbidity isn’t something that only happens at the time of birth — it must start with the early identification of high-risk cases like these, followed by community-based support to avoid catastrophic outcomes for mothers and infants.”

For the study, Dr. Declercq and colleagues utilized data from a statewide database that linked unscheduled hospital visits — including trips to the emergency department as well as observational hospital stays — by 774,092 pregnant patients to births and fetal deaths in Massachusetts between October 2002 and March 2020.

About 18 percent of patients had one emergency visit to the hospital, nearly 7 percent had two visits, 3 percent had 3 visits, and 3.3 had four or more visits. About 44 percent of patients who sought emergency care four or more times during pregnancy visited more than one hospital. This group was 46 percent more likely to experience SMM than patients who sought less emergency care and visited fewer hospitals during their pregnancy. Patients were also more likely to seek emergency care during the first eight weeks and last eight weeks of their pregnancy.

The researchers also observed several racial, economic, and age-related disparities among the patients who used emergency care multiple times during their pregnancy. High utilization of unscheduled hospital care was most associated with women under 25 years old, Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients, and those who were born in the US, unmarried, or who had an additional health condition or opioid-related hospitalization in the year prior to their pregnancy. Some of these individuals have visited up to six different Massachusetts hospitals for emergency care, the researchers say.

“Our study shows for the first time that those who use the emergency room more during pregnancy are more likely to be people of color whoare at significantly higher risk of experiencing a potentially life-altering morbidity event around the time of childbirth,” says study senior author Dr. Pooja Mehta, adjunct assistant professor of obstetrics & gynecology at BU’s Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine and vice president of population health at Cityblock Health. “We need to do much more than provide these individuals a follow-up prenatal visit; our actions have to be timely and address root causes and fragmentation in the system to impact the layers of structural racism that we already know contribute to maternal morbidity.”

The team hopes these findings bring attention to the high rates of emergency care visits driven by unmet needs — a public health issue that is not well documented — and encourage researchers, healthcare providers, policymakers, and reproductive health advocates to envision ways to strengthen or compensate for traditional prenatal care that falls short of meeting pregnant patients’ health needs.