It’s not a bad thing if you pick a toasted bagel for breakfast, while your partner chooses eggs. In fact, according to a new study from the University of Waterloo, that difference could help you lose some weight. The study, “Modeling sex-specific whole-body metabolic responses to feeding and fasting” appears in Computers in Biology and Medicine.

The study, which employed a mathematical model of men’s and women‘s metabolisms, showed that men’s metabolisms respond better on average to a meal laden with high carbohydrates like oats and grains after fasting for several hours, while women are better served by a meal with a higher percentage of fat, such as omelets and avocados.

“Lifestyle is a big factor in our overall health,” said Stéphanie Abo, an Applied Mathematics Ph.D. candidate and the lead author of the study. “We live busy lives, so it’s important to understand how seemingly inconsequential decisions, such as what to have for breakfast, can affect our health and energy levels. Whether attempting to lose weight, maintain weight, or just keep up your energy, understanding your diet’s impact on your metabolism is important.”

The study builds on an existing gap in research on sex differences in how men and women process fat. “We often have less research data on women’s bodies than on men’s bodies,” said Anita Layton, a professor of Applied Mathematics and Canada 150 Research Chair in Mathematical Biology and Medicine.

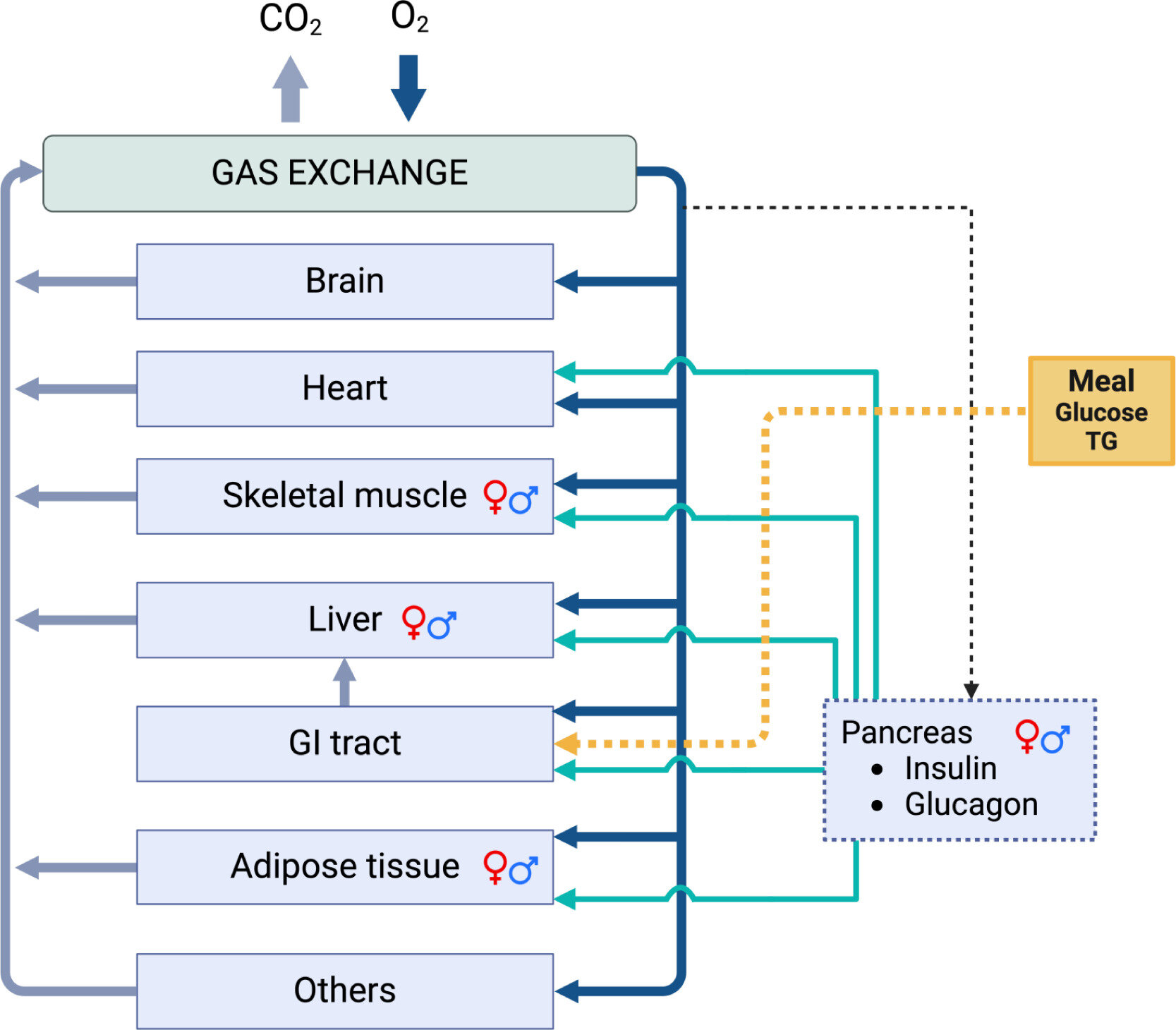

“By building mathematical models based on the data we do have, we can test lots of hypotheses quickly and tweak experiments in ways that would be impractical with human subjects.”

“Since women have more body fat on average than men, you would think that they would burn less fat for energy, but they don’t,” said Layton. “The results of the model suggest that women store more fat immediately after a meal but also burn more fat during a fast.”

Going forward, the researchers hope to build more complex versions of their metabolism models and extend beyond the consideration of biological sex by incorporating an individual’s weight, age, or stage in the menstrual cycle.

More information:

Stéphanie M.C. Abo et al, Modeling sex-specific whole-body metabolic responses to feeding and fasting, Computers in Biology and Medicine (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109024

Citation:

Metabolic model for feeding and fasting shows how nutrition differs for men and women (2024, October 7)

retrieved 7 October 2024

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-10-metabolic-fasting-nutrition-differs-men.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.