For 12 years, Paul Stroud’s done everything he can to combat the effects of Parkinson’s disease. He had a pair of stimulators implanted deep in his brain. He takes the standard medications to treat symptoms. He even briefly tried out tai chi.

Over the past couple of months, however, the 71-year-old’s discovered an effective form of therapy he may have never tried otherwise—one that takes him vertical.

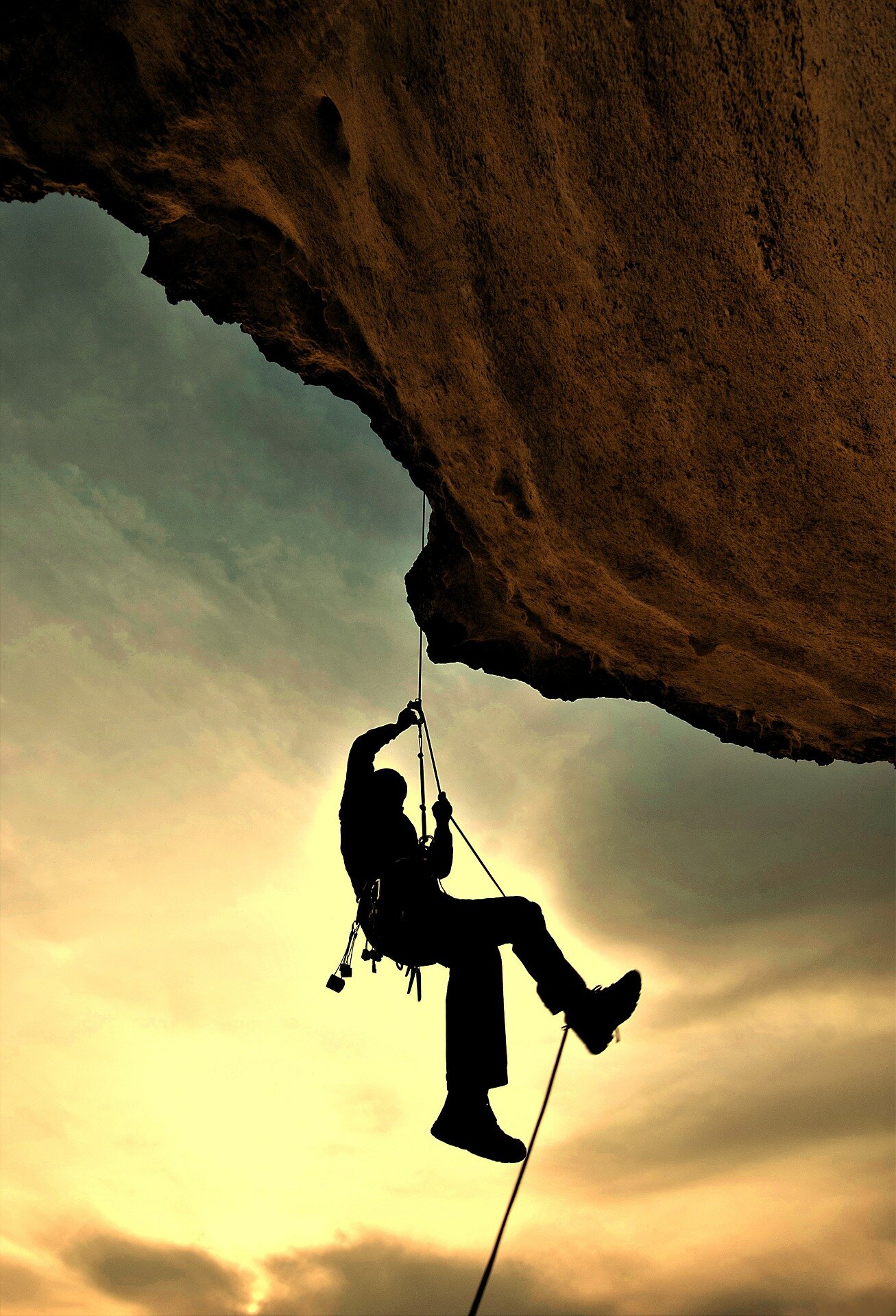

When Stroud sheds his walker to put on a harness and scale a climbing wall at Movement gym in Golden, his battle with Parkinson’s—and the issues with balance and tremors that accompany it—dissipates as he pulls himself up.

“I don’t do real well with heights, so I’m not a big fanatic about going up the wall. But it’s fun, and it’s rewarding,” the Littleton resident says. “I’ve steadily improved in my climbing, and I’m doing routes where I might give out and try it again, and then go farther. Get all the way up there.

“… The immediate feeling when I get to the top is, ‘Phew, okay, I get to go back down now.’ But there’s also a sense of accomplishment, and that I’m doing some good for myself to (stave off) the effects of this disease.”

Stroud is part of a weekly climbing session for people with Parkinson’s disease that meets every Tuesday morning in Golden. The group is a local chapter of Virginia-based Up Ending Parkinsons. The non-profit provides guided rock climbing for people living with the neurodegenerative disorder that affects an estimated one million Americans.

The group that gathers in Golden was started by Doug Redosh, a 70-year-old Applewood resident.

The former neurologist was diagnosed about six years ago and has an understanding of the disease after watching his patients battle through it—as well as his father. He’s participated in climbing for about 50 years, so combining his athletic interest with his battle against the disease was a natural fit.

“When I read an article in Outside Magazine in February about Up Ending Parkinsons, that was a new lease on life for me,” Redosh said. “That got me going and motivated me to start this climbing program out here. And since doing that, and increasing the frequency at which I climb, I feel better overall.

“There’s the benefits of strength, balance, coordination, etc. There’s the benefits of camaraderie and companionship. And to see a person like Paul climb the wall, with the neuropathy he suffers from and considering part of one of his feet is amputated, is really impressive. I’m getting that out of it as well: I’m benefiting from other people’s benefits and improvements.”

Exercise is known as one of the best weapons in limiting the effects of the disease and creating dopamine that is low for those with Parkinson’s, and sport climbing’s specific impact has been documented in several recent studies.

One study published in 2022 stated that climbing “offers an effective and feasible training method that may positively affect (people with Parkinson’s) overall perceptions of physical and psychosocial health status.”

Another study released earlier this year, also by researchers at the Medical University of Vienna, took that premise further with the conclusion that “sport climbing improves gait speed during normal and fast walking, as well as functional mobility in people with Parkinson’s disease.”

Up Ending Parkinsons conducted its own study, which was done through Marymount University, and tracked the progress of some of the program’s climbers over 24 sessions. The results will be presented on Nov. 1 at the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine’s annual conference in Dallas. Up Ending Parkinsons president Molly Donelan-Cupka says it has “significant findings.”

“The beautiful thing about climbing is that it takes every different aspect of how the body functions and moves, and puts it all into play to be able to climb up the wall,” explained Dr. Drew Falconer, the director of the Inova Parkinson’s & Movement Disorders Center.

“You have to have cognitive thinking and planning, you have to have core strength, arm and finger strength, leg strength. You have to have balance and coordination; you have to be able to go up and come down. That’s why it works beautifully with Parkinson’s, is because it’s a cohesive approach to exercising every aspect of the body.”

All of which is why members of Redosh’s group see their participation on Tuesday mornings as critical to their long-term health.

Sean, a 56-year-old Castle Rock resident who requested his last name not be used in this story, joined the group a couple of months ago after receiving his diagnosis in late April. He is a former Marine and Gulf War veteran who spent several decades as a corporate pilot.

But when his diagnosis forced his abrupt retirement from flying, he found himself in a funk. He languished around his house and slept in late. Then, with some prodding from his wife, a switch flipped.

“I wasn’t going to sit and have a pity party and keep feeling sorry for myself,” Sean said. “I just can’t live like that, just letting the disease take over my mind. I wanted to take control back.”

So Sean started climbing with Redosh’s group, and also took up boxing, high-intensity interval training and yoga, in addition to picking weight-lifting back up. He now works out six or seven days a week, determined to use climbing and other exercise to help him live a full, happy life.

Stephen Nash, a 60-year-old from Centennial who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s a year ago and recently joined Redosh’s group, feels a similar optimism after rappelling down the wall.

“This helps my fitness level, and it also seems to stabilize my Parkinson’s symptoms somewhat,” Nash said. “Making those big movements on the wall, it’s really good, because Parkinson’s tends to make (your limbs) draw in and become small and stiff. So reaching, and using all those muscles big and small, I’ve really felt it helps me.”

Redosh hopes his group, which has grown from a couple of people to about 10 weekly participants, is just getting going. They are planning an outdoor climb in November, by which time he hopes to have more people signed up.

As the campaign to end Parkinson’s gets more prominent nationally—this summer, President Joe Biden signed into law the National Plan to End Parkinson’s Act, a first-ever federal initiative aimed at finding improved treatments for the disease—Donelan-Cupka also eyes expansion for Up Ending Parkinsons.

The organization, which was founded in 2012 and officially became a non-profit about three years ago, currently has 18 locations across 12 states, but Donelan-Cupka says the program is primed for explosive growth. She wants it to be in over 100 gyms in a few years, with the goal to have at least two in every state.

Colorado will soon be getting its second Up Ending Parkinsons chapter, at the Movement gym in Englewood. It’s scheduled to begin next month.

“I’m really excited about seeing the program itself continue to grow and seeing people like myself gaining self-confidence,” Redosh said. “Not just improvements in climbing, but seeing improvements in strength and knowledge and the idea that (a Parkinson’s diagnosis) does not have to keep you from doing life and doing inspiring things.”

2024 MediaNews Group, Inc. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Citation:

How a Colorado Parkinson’s group uses climbing to help stave off effects of the disease (2024, September 27)

retrieved 28 September 2024

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-09-colorado-parkinson-group-climbing-stave.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.